Hebrew and You with Lee M. Fields — A Postscript and a Christmas Note

Postscript: LXX and Masoretic Text

Last month’s post generated some interest from readers on the Septuagint (LXX). Some may wonder whether the LXX or the Hebrew is more reliable — or perhaps another text tradition, for that matter. The LXX does indeed represent a different tradition of the Hebrew Bible text. The Dead Sea Scrolls at times agree with MT, at others with the LXX, and sometimes vary from both. I conclude that the Masoretic Text (MT) tradition of the Hebrew Bible should be the basis for study and translation.

Why should the MT tradition be preferred? The bottom line for me is that the Jews themselves set out to wade through the various traditions 2,000 years ago, and their conclusions have come down to us as what we call the Masoretic Text. So, most Protestants, for example, accept as the authoritative word of God the canon of the MT, the 39 books of the Christian Old Testament, and do not include the deutero-canonical books. Similarly, the Jews made decisions on the best textual tradition (for example the longer version of the David and Goliath story, as mentioned in the previous post). The reasons for the choices are not known, but the decisions were not made in ignorance. Another piece of evidence for the antiquity and authenticity of the MT tradition is the preservation of archaic forms (parts of words that were no longer used in Hebrew but were preserved anyway).

These are good reasons for having a deep respect for the MT. There may be some fine tuning modern scholars can make as they learn new things about ancient culture, language, and literature, as well as about the Hebrew language itself. But the Jews then were very familiar with the literature, language, and text traditions in a way that is difficult to replicate. I think the best course of action is to deviate from the MT only rarely and as a last resort.

Christmas Note: Who is the Child-Son in Isaiah 9:6 (Hebrew 9:5)?

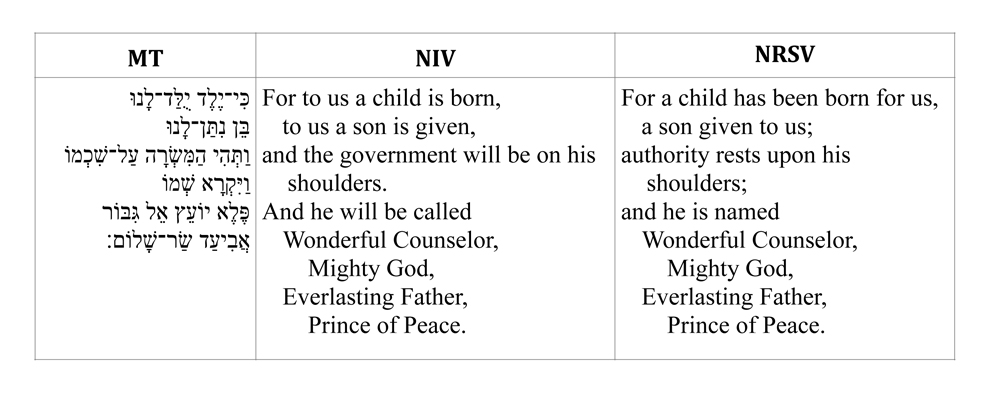

Isaiah 9:6 is well known and often quoted at Christmas time. The angel alludes to the passage in the Christmas story, “Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord” (Luke 2:11 [NIV]). Also the clear allusion to this passage by Gabriel in Luke 1:32–34 makes clear that Isa 9:6 was understood as Messianic by the writers of the NT. Compare, though, the Hebrew, NIV, and NRSV.

Isaiah 9:6 (Hebrew v. 5) in MT, NIV, and NRSV

There are two main differences between the two English versions given above: first, the word order of the first two lines, specifically with respect to the location of the words “child” and “son,” and second the tense of the verbs in the second half of the verse.

Word Order

In English, default word order is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO). In a Hebrew sentence, the default word order is Verb-Subject-Object (VSO). This is seen most consistently in the Wayyiqtol (narrative past tense) and especially in clauses introduced by particles, such as אֲשֶׁר (ʾăšer, “which”) and כִּי (kî, “that, because”). In this verse the first two clauses are governed by the כִּי. The Hebrew, however, rather than being the default VS(O), has the word order SV(O).

The English translations of this verse often put the prepositional phrase “to us” first (NIV, KJV, ESV). This, however, brings the “to us” into prominence. The Hebrew places no prominence on this phrase. Others put “child” first (NASB, NLT, NRSV). This matches the Hebrew word order, but in English this is the default order with nothing special, while the Hebrew has placed child at the beginning, called fronting.

Why is the Hebrew word order not the default? The fronting of “child,” as well as that of “son” in the next clause, serves to relate the clauses to the context. This child-son is marked at the referent of the working of the Lord on behalf of his people described in vv. 2-5 (Hebrew vv. 1-4). It is not so much emphasis as it is clarification.

The Tense of the Verbs

Both English translations given in the chart above are possible, but they do represent two understandings of the identity of the child-son. The NIV renders the first two verbs as present perfect time and the last two verbs as future, while the NRSV renders the first two as past perfect and the last two as present. In other words, for each pair of verbs the NRSV fixes the time one slot earlier. For the NIV, then, 9:6 is predicting an event future to the time of speaking and for the NRSV 9:6 is describing an even present in the time of speaking.

For the discussion of the verbs that follows, I refer the reader to Randall Buth, Living Biblical Hebrew ג (Jerusalem: Biblical Language Center, 2006), 143–7, and to Jan Joosten, The Verbal System of Biblical Hebrew (Jerusalem: Simor, 2012), 42-50.

יֻלַּד and נִתַּן

The verbs יֻלַּד (yullad, “is born”) and נִתַּן (nittan, “is born”) are in the form called Perfect, or better Qatal. Beginning Hebrew students learn that the default time frame for the Qatal verb is past time. The term “Perfect” actually refers to aspect, a viewpoint of the action. In particular, the Perfect aspect describes action viewed as completed. The default function of the Qatal is to mark action that is both past time and perfective aspect.

Past time, perfective action is not, however, the only option. The action of the Qatal form is used to indicate action prior to another action; often called “anterior.” This means that the action of the Qatal verb can occur in any time frame. If the context is set in the future, the Qatal verb can be in the future, but it will normally still be prior to another even later action. This is exactly what is happening here. The promise of 9:1 will be fulfilled after the actions of these two Qatal verbs in v. 6.

וַתְּהִי and וַיִּקְרָא

The last two verbs, וַתְּהִי (wattehî, “will be”) and וַיִּקְרָא (wayyiqrā̄ʾ, “will be called”) are the form Wayyiqtol. In narrative, this verb form is the normal past tense that moves a story forward. The NIV, along with most English versions, translate these verbs in 9:6 as future time. This translation is not incorrect. The Wayyiqtol form can also be continuative, that is, the actions carry forward from the previous verbs. The NRSV also takes these as continuative when they render with present tense verbs, “authorities rest … and he is named.” In both NIV and NRSV they are still subsequent to the first two verbs. The difference is the time frame of the first pair of verbs.

The Identity of the Son

Both the NIV and NRSV translations are possible. The LXX translates the first three verbs with the Aorist tense, the default for simple past time and the fourth verb as Present. Second century AD Jewish Greek versions varied from this. Aquila’s translation has four Aorists, while Symmachus’ has three Aorists and a Future! Clearly the Jews felt some flexibility in the Hebrew verbs.

The Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 94A, records the view that this child-son was Hezekiah. The NRSV can be read to support this view. On the other hand, the NT attributes the fulfillment to Jesus, obviously a time far in the future with respect to Isaiah. This understanding of the timing of the verbs actually fits the context better. Isaiah 9:1 (Hebrew 8:23) sets up the time frame as future for the poem that follows beginning in 9:2 (Hebrew 9:1). Hezekiah was a contemporary of Isaiah, but might still be the child-son with respect to some future period of his life, but the epithets describing this child-son and his rule do not fit Hezekiah nor any other merely human descendant of David. The NIV translation of Isa 9:6 makes this choice clear. The NT identification of this child-son with Jesus the Messiah is the best option. I refer the reader to John N. Oswalt, Isaiah [NIVAC; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003], 159–61, or his fuller treatment in Isaiah 1–39 (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1986), 244–48.

Not only at Christmas time, but at all times, it is well to remember the promised child-son, the Messiah, Immanuel, who was the fulfillment of promise and God’s gift to all mankind through the Jewish nation.

This completes the first year of this blog. Thank you for reading. I pray you have found it valuable. May you have a Merry Christmas.

(Image: The Adoration of the Shepherds; Gerard van Honthorst [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

________________________

Lee M. Fields writes about the biblical Hebrew language, exegesis, Hebrew translation, and related topics at Koinonia. A trained Hebrew scholar, his education includes a Ph.D. from Hebrew Union College. He is the author of Hebrew for the Rest of Us (Zondervan, 2008) and An Anonymous Dialogue with a Jew (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012). He currently serves as Professor of Bible and Chairman of the Department of Biblical Studies at Mid-Atlantic Christian University in Elizabeth City, NC.

Lee M. Fields writes about the biblical Hebrew language, exegesis, Hebrew translation, and related topics at Koinonia. A trained Hebrew scholar, his education includes a Ph.D. from Hebrew Union College. He is the author of Hebrew for the Rest of Us (Zondervan, 2008) and An Anonymous Dialogue with a Jew (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012). He currently serves as Professor of Bible and Chairman of the Department of Biblical Studies at Mid-Atlantic Christian University in Elizabeth City, NC.

Learn more about Lee's innovative work in biblical languages and instruction.

(Image: Bernini's David, (1623), http://arth1700.wordpress.com/2012/10/.)

Thank you!

Sign up complete.