Hebrew and You with Lee M. Fields: Hebrew Verbs and Hebrew Stories

The Old Testament is full of gripping stories that are quite memorable. Understanding something of the Hebrew verbs can enhance one’s reading of Hebrew narrative. I would like to recommend two resources: Jan Joosten, The Verbal System of Biblical Hebrew (Jerusalem: Simor, 2012) and Robert Chisholm, Interpreting the Historical Books (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2006).

Hebrew Basics

For those readers who might not know it, the Hebrew letter Waw is the most common Hebrew word by far. It is used a conjunction most often translated “and,” though it has other important functions. Most notably, it is part of the Hebrew verbal system. Unlike English, this Waw is always prefixed to a word; it never stands alone.

The Hebrew verbal system can be divided into two main categories that go by many names; I like to use Real, or Indicative, on the one hand, and on the other hand Irreal, or Non-Indicative (irreal does not mean unreal!). The Irreal category includes both Modal (or Potential) and Volitional actions (those involving the will, such as commands; for simplicity, we will not discuss Volitional forms here).

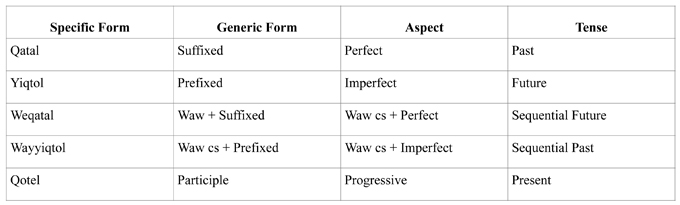

The Hebrew verbs themselves cover all these situations with five forms. Again, grammarians use a number of different naming systems to discuss these verbs. These names can be based on the verbal form, aspect, or tense.

I find the specific from names to be the simplest way to be precise.

The foundational form of Hebrew narrative is the Wayyiqtol. This verb form introduces what many scholars call “offline clauses.” It moves the plot of a story line forward, as a train moving along a track. Clauses beginning in other ways stop the action of the story for some reason, as a train stopping at a depot. These clauses can be referred to as offline clauses, respectively. When the action stops, the offline clauses are supposed to get our attention. It is sort of like getting off the train while it is stopped at the depot and walking around to see what is there.

Offline clauses frequently give background information, parenthetic information, or conclusions. Paying attention to the Hebrew structure can help us understand how the author wrote the story, when the structure of the story might easily be missed in translation.

Let’s look at an example.

1 Sam 16:14-24

Verse 14 begins with an offline clause, Waw + non-verb. This marks the beginning of a new episode. Then in v. 23, none of the verb forms is Wayyiqtol, even though most versions translate these as simple past tense verbs. Instead they are all Weqatal forms (bolded), also marking the end of the episode.

None of this is earth shattering; the change of episode is also indicated by the change in location in 16:14 and 17:1. (Remember: I am not blasting our English versions; they are extremely well-done. It is just that some things are difficult to translate in a natural way or are not as obvious in English.) What is interesting is the meaning of the verb forms. In v. 14 the first clause has the Qatal, which indicates past time with respect to a reference point. For this reason some versions translate the verb “had departed” (NIV) or “had left” (NLT) instead of the simple past (ESV, NASB, NRSV). That reference point would seem to be the action of the verb in the second clause.

The second clause has the form Weqatal. The Weqatal and Yiqtol have about the same range of meaning. Generally speaking they indicate incompleted or modal (Irreal) action in the timeframe of the context. The second verb is usually translated as a simple past (ESV, NIV, NASB, KJV, NRSV). Why then does the NLT translate, “the Lord sent a tormenting spirit that filled him with depression and fear”? It is because the Weqatal here has this incompleted (Irreal) action notion. In other words, this torment was not a one-time event, but was recurring.

Verse 15 has the Wayyiqtol form: now the action of the episode begins. It was apparently during one of these attacks (“is tormenting” [ESV]; the Qotel form is the normal way to portray action in progress at the time of speaking) that Saul’s servants offered to help Saul. The speech acts are not part of the moving plot, but are depots along the way. The verbs of speaking keep the dialogues moving forward through v. 22.

In v. 23 there are five clauses with verb forms (plus one verbless clause, which does not concern us here). Each of them is Weqatal. This series of offline clauses brings this short episode to a close; the verse forms the destination on our rail journey. By means of the Weqatal clauses the author presents the series of actions as open-ended. This is why the ESV (similarly KJV) begins the verse with “and whenever”; the simple past verbs that follow are not meant to be understood as completed acts, but were the actions that took place repeatedly whenever Saul was overcome. The NIV, NASB, NRSV, and NLT make this more clear by translating all the verbs as modals: “[And it would be when …, that] David would take … and would play … and Saul would feel better … and the spirit would depart.”

The reader is left with this portrait of David and of Saul. Verse 23 is sort of like a short movie clip displaying to the reader’s mind the repetitive series of actions. What a contrast between the recurring bouts of Saul with the evil spirit and the ability of David to comfort him! What a contrast between the conclusion of the previous episode and the ending of this one. In 16:13 David is anointed and the then the author states that “the Spirit of the Lord rushed upon David from that day forward.” These are a series of Wayyiqtol forms marking simple, yet climactic, sequential, online actions. Now this episode begins and ends with offline clauses that are a moving picture of the result of the Spirit of the Lord that was upon David. David’s character is recited in v. 18 and Saul valued him. David was able to enter into the court of Saul and minister to a king, who had been disobedient and was rejected by the Lord. This behavior of the Spirit-filled David sets up many events in the coming chapters, when Saul would become David’s mortal enemy.

As I mentioned before, the stops along the journey are intended to get our attention. The dialogues are some of those stops. In the dialogs David is portrayed as a man loyal to the Lord. The Weqatal verb forms are other stops. In the conclusion David is portrayed as loyal to Saul. Both of these help illustrate the result of the rush of the Spirit of the Lord upon David. Today the Spirit lives in all Christians and gives power to serve the Lord and mankind. May we demonstrate our loyalty as David did.

________________________

Lee M. Fields writes about the biblical Hebrew language, exegesis, Hebrew translation, and related topics at Koinonia. A trained Hebrew scholar, his education includes a Ph.D. from Hebrew Union College. He is the author of Hebrew for the Rest of Us (Zondervan, 2008) and An Anonymous Dialogue with a Jew (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012). He currently serves as Professor of Bible and Chairman of the Department of Biblical Studies at Mid-Atlantic Christian University in Elizabeth City, NC.

Lee M. Fields writes about the biblical Hebrew language, exegesis, Hebrew translation, and related topics at Koinonia. A trained Hebrew scholar, his education includes a Ph.D. from Hebrew Union College. He is the author of Hebrew for the Rest of Us (Zondervan, 2008) and An Anonymous Dialogue with a Jew (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012). He currently serves as Professor of Bible and Chairman of the Department of Biblical Studies at Mid-Atlantic Christian University in Elizabeth City, NC.

Learn more about Lee's innovative work in biblical languages and instruction.

Thank you!

Sign up complete.