The Symbolic Language of Revelation

Richard Hays rightly observes that “interpreters have strained to make sense of the phantasmagoric imagery of the Apocalypse.” In simplest terms, Revelation uses “picture language” to draw in the audience, inform them about what is real and what is a lie, and persuade them to live in faithful discipleship to Jesus. The reader sees, hears, and experiences the drama through a complex, multicolored literary creation. To appreciate fully the picture language of Revelation, the reader must understand how Revelation proposes to communicate truth, the nature of the book’s symbolic language and how it functions, and the primary contexts for grasping this type of language.

The Way Revelation Communicates

In Rev 1:1, John’s terminology suggests he is using picture language as the primary means of receiving and communicating the vision: “The revelation (ἀποκάλυψις) from [or “of”] Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show (δείκνυμι) his servants what must soon take place. He made it known (σημαίνω) by sending his angel.” Beale has developed the connection with Dan 2 (LXX) to demonstrate that the primary manner of communication in Revelation is symbolic, in both John’s reception and communication of the vision:

"The symbolic use of σημαίνω in Daniel 2 defines the use in Rev. 1:1 as referring to symbolic communication and not mere general conveyance of information. Therefore, John’s choice of σημαίνω over γνωρίζω (“make known”) is not haphazard but intentional. Regardless of which Aramaic or Greek word or version is in view, however, the allusion to Dan. 2:28–30, 45 indicates that a symbolic vision and its interpretation is going to be part of the warp and woof of the means of communication throughout Revelation."

John also adds that God gave Jesus the revelation to “show” (δείκνυμι) his servants what is to come (Rev 1:1; cf. the seven uses of the term elsewhere in 4:1; 17:1; 21:9–10; 22:1, 6, 8). As we will see below, this term carries the idea of communicating through the senses, and this is confirmed by John’s testimony that he “saw” the heavenly vision. Just as God communicated to Daniel through symbols, so he communicates to (and through) John in the same manner.

We will explore in a later chapter how to interpret symbolic language (see Ch. 10) but here we conclude with Beale that Revelation’s picture language should be taken seriously. While some interpreters presume a literal reading unless the context demands that we interpret symbolically, this cluster of terms in the opening verse and the connection to Daniel encourages us to take the opposite approach. In Beale’s words, “we are told in the book’s introduction that the majority of the material in it is revelatory symbolism (1:12–20 and 4:1–22:5 at the least). Hence, the predominant manner by which to approach the material will be according to a nonliteral interpretative method. Of course, some parts are not symbolic, but the essence of the book is figurative.”

Since John communicates in picture language, it stands to reason that he is passing on what he has seen and heard in his vision. Visual and auditory language pervades the Apocalypse (e.g., 22:8: “I, John, am the one who heard and saw these things. And when I had heard and seen them, I fell down to worship at the feet of the angel who had been showing them to me”). Revelation primarily uses three verbs to express John’s experience of seeing: βλέπω (13x), θεωρέω (2x), and especially ὁράω (61x).50 John, who has been “shown” the vision, now “sees” it. John is a visual witness who testifies faithfully to “everything he saw” (1:2). Interestingly, Ureña notes that John avoids verbs that have the opposite meaning (e.g., “to conceal,” “to hide,” “to disappear,” etc.) unless they are needed to make a specific point (e.g., the “hidden manna” of 2:17).

Guffey highlights the book’s visuality. It is a vision and within this vision we find a multitude of images. It is indeed “a work of visual theology.” He argues that John uses images in ways similar to the three uses of ekphrasis in the ancient world with ekphrasis being defined as “the verbal representation of visual representation.” The uses include making a reality present, grounding the orator’s authority, and captivating the audience emotionally. This leads naturally into the function of Revelation’s symbolic language, which uses imagery to combine cognitive and emotional appeals for the reader to experience and participate in the reality of the vision. Visual imagery plays a significant role in the divine author’s attempt to dramatically transform the audience’s perception of spiritual reality.

But Revelation does not just engage the visual senses; it also engages our sense of hearing. Mangina writes:

"The Apocalypse is a book of auditions. Trumpets sound, thunderclaps boom, angels cry out—almost always “with a loud voice.” The absence of sound can be equally important. Silence in heaven marks a period of expectant waiting for fresh revelation (8:1), and the death of Babylon will later be denoted by the sound of silence—musicians, singers, the voices of the bridegroom and the bride all strangely quieted (18:22–23). But for the most part Revelation is a very loud book, situating us in the midst of an extraordinary aural universe."

Revelation was both a spoken and a heard revelation: “to his servant John, who testifies to everything he saw—that is, the word of God and the testimony of Jesus Christ. . . . I, John, am the one who heard and saw these things. And when I had heard and seen them . . .” (1:1–2; 22:8, emphasis added). Forms of the verb ἀκούω (“I hear”) occur almost fifty times in Revelation and emphasize its auditory nature. In addition, messengers speak, choruses sing and recite, prophetic instructions are given, instruments play, voices voice and sound abounds in the Apocalypse.

We should always remember that Revelation was originally meant to be read aloud and heard by a group of believers gathered for worship. The first of seven beatitudes is pronounced on “the one who reads aloud the words of this prophecy” and “those who hear it and take to heart what is written in it” (1:3). Rather than individuals reading alone silently, we should imagine a corporate audience hearing the book read aloud. As a result, we must attend to auditory elements of the book whenever possible—verbal repetitions, rhythmic patterns, alliteration, silence, and so on.

To be sure, the auditory power of Revelation can be just as transformative as its visual:

"The auditors who came together to hear the Apocalypse were summoned to a transformative experience. Those first ancient auditors of the Apocalypse came together not merely to be informed, but to be transformed, to undergo a collective change in consciousness, an aspiration that makes modern individual and group reading practices trivial by comparison, with the possible exception of the reading of wills. Reading the Apocalypse aloud, and hearing the Apocalypse read aloud, was effectual: through exhortations and exclamations, threats and thunder, the reading of the Apocalypse moved its hearers, effected them; the text did something to them."

While Revelation uses picture language to appeal to the senses, it also communicates through a nuanced and complex series of literary expressions that narrative and rhetorical approaches are designed to notice. Along with metaphor and simile, Koester notes the use of antonomasia, hyperbole, metonymy, and polysyndeton in Revelation. James Resseguie has a lengthy discussion of the more common literary terms and narrative devices used in Revelation, including metaphors and similes, progressions, verbal threads, chiasm, inclusio, numbers and numerical sequences, setting, characters, point of view, plot, narrator, and structure. DeSilva has argued extensively for a rhetorical reading of Revelation that considers the many ways John seeks to persuade his audience. At this point we need to explore further the nature of Revelation’s symbolic language.

The Nature of Symbolic Language

All these means of communication shows that Revelation is communicating at

several different levels. Drawing on Poythress, Beale identifies four such levels:

- Linguistic—the textual record itself

- Visionary—John’s actual visionary experience (i.e., what John saw)

- Referential—the historical identification of what is seen in the vision (i.e., what the vision refers to in history)

- Symbolic—what the symbols in the vision say about the historical referent

Interpreters are often clear about what John saw but are not always clear about what it refers to or what the symbols say about the referent. At times interpreters even collapse the referential and symbolic in a more literalistic interpretive approach so that the visions are direct representations of historical events. To unpack the nature of Revelation’s symbolic language we begin with what lies at the heart of symbol—comparison.

Symbols are “figurative comparisons.” Revelation uses three basic forms of comparison. Beale explains: “Formal metaphor [is comparison] in which the literal subject is connected to the figurative subject by a form of ‘to be’ (‘The Lord is my shepherd who loves me’). Simile is when the two subjects are linked by ‘like’ (‘The Lord is like a shepherd who loves me’). Hypocatastasis occurs when the literal subject is not stated but assumed ([The Lord who is like] ‘The shepherd loves me’).” Sometimes these comparisons have one clear referent (e.g., 1:20: “the seven lampstands are the seven churches”), while at other times more than one point of comparison seems intended (17:9–10a: “The seven heads are seven hills on which the woman sits. They are also seven kings”). Yet even those symbols with a single referent can be just as evocative and powerful as those with multiple referents (e.g., Jesus Christ as the slain but risen Lamb).

The comparison at the heart of symbolic language is essential in Revelation where John is attempting to convey spiritual realities to his audience. He is moving from what we know to what we have never experienced or perhaps never even heard about. In essence, this is what happens anytime we attempt to do Christian theology. Can we really say anything about God without using metaphorical language? Ian Paul writes, “Metaphor is the centre of all Christian theology, and in that sense Revelation is the most Christian text in the New Testament.”

In Revelation we see symbolic language applied noticeably to colors and numbers. Gorman notes that in the Apocalypse “colors function more like images than adjectives, and the numbers more like adjectives than numbers.” The following table highlights the symbolism of colors often observed by scholars:

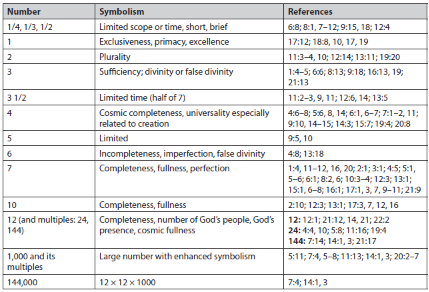

As was common in the ancient world, John’s audience would have also understood numbers to carry symbolic significance. The table on the next page shows some of the symbolic values noted by scholars But Revelation goes beyond simply using numbers in the text to signify completeness or imperfection or the like. John uses numbers in several other important ways in his carefully crafted literary masterpiece. First, certain words or events occur with particular frequencies, thus giving them added significance. For instance, the divine title consists of a present, past, and future dimension: “who is and who was and who is to come” (1:4, 8; 4:8; cf. 11:17; 16:5). We also see the Lord God Almighty described as “Holy, holy, holy” (4:8). God is often praised in threes (e.g., 4:11; 12:10; 19:1). Christ and his work are sometimes described using threes (1:5; 22:13).

The same applies to the number four with four corners, four winds, four living creatures, a four-plus-three pattern to the judgments, a fourfold formula drawn from the related terms tribe, language, people, multitudes, kings, and nation (a formula which occurs seven times: 5:9; 7:9; 10:11; 11:9; 13:7; 14:6; 17:15), a cargo list of twenty-eight items (4 × 7), and certain names of God and Christ are repeated four times, along with four references to the seven spirits.

The number seven is used extensively in this manner. There are seven beatitudes, seven “sickles” in Rev 14, seven times God is titled “Lord God Almighty,” and seven occurrences of “Christ,” “testimony of Jesus,” “prophecy,” “I am coming,” “sign,” “endurance,” and “cloud.” There are seven times that “elders” and “living creatures” are named together, while Jesus and the Spirit and the saints are all mentioned fourteen times (2 × 7). In addition, there are seven messages to the churches and three series of seven judgments. Doxologies may also be threefold, fourfold, or sevenfold.

We also see a similar pattern with the number twelve. There are twelve tribes of Israel and twelve apostles of the Lamb. Twelve is also the number of God’s people, “squared for completeness, multiplied by a thousand to suggest vast numbers” (i.e., 144,000). Twelve is also mentioned twelve times in the description of the New Jerusalem in 21:9–22:5, a reminder of the completeness of the people of God in the new creation. These examples show that John used numerical composition carefully and intentionally throughout the book.

Second, Revelation draws on the mathematical significance of square, triangular, and rectangular numbers. John consistently uses square numbers to represent the things of God, especially the people of God (e.g., 144 and 1,000), while he uses triangular numbers to designate the opponents of God (e.g., 666). Bauckham applies this mathematical reality to the number 666 (a rare doubly triangular number) in support of identifying Nero as the beast.

Third, we also see the use of isopsephism or gematria, which refers to calculating the numerical value of words and names by adding up the value of their letters. For example, the number of the beast, 666 in 13:18, can quite naturally be viewed as reference to Nero Caesar (NRON KSR calculated in Hebrew). Interestingly, using gematria, the name of Jesus (IESOUS) is calculated as 888, a number often associated with abundant and overflowing blessings. Such a practice was not uncommon in the ancient world, and John’s readers would have been familiar with it.

John’s symbolic language, including his use of colors and numbers, clarifies his story and enhances its rhetorical power and realism, while theologically reminding the reader that God is in control and his victory over evil is certain. For example, Beale notes that four, seven, and twelve “figuratively convey the notion of God’s ordering of the world and his sovereignty over it.” Yarbro Collins concludes that John uses these numbers to represent the divine “net in which the Satanic forces are captured, surrounded and confined on all sides,” thereby showing God’s ultimate victory over evil.

The Purpose and Function of Symbolic Language

Revelation’s picture language creates a “symbolic world which readers can enter and thereby have their perception of the world in which they live transformed.” Creating a symbolic world was necessary because the Roman world was full of images with enormous transformative power. In a typical Greco-Roman city, believers were surrounded by statues, inscriptions, temples large and small, image-bearing coins, rituals, festivals, altars, friezes, and various other iconography supporting the empire as ultimate reality. This does not even include the “verbal imagery” such as speeches, songs, prayers, pledges, and the like.

As believers gathered in house churches to hear the book of Revelation read (and all who have heard it since), they would enter a rival symbolic world with its own set of “Christian prophetic counter-images.” The purpose was to purge the Christian imagination, “refurbishing it with alternative visions of how the world is and will be.” Bauckham explains:

"[Revelation with its imagery] tackles people’s imaginative response to the world, which is at least as deep and influential as their intellectual convictions. It recognizes the way a dominant culture, with its images and ideals, constructs the world for us, so that we perceive and respond to the world in its terms. Moreover, it unmasks this dominant construction of the world as an ideology of the powerful which serves to maintain their power. In its place, Revelation offers a different way of perceiving the world which leads people to resist and to challenge the effects of the dominant ideology. Moreover, since this different way of perceiving the world is fundamentally to open it to transcendence it resists any absolutizing of power or structures or ideals within this world. This is the most fundamental way in which the church is called always to be counter-cultural."

The prevailing Greco-Roman culture with its plethora of idolatrous images simply could not be debated out of existence; it had to be overpowered by an alternative vision that was even more captivating. This alternative vision then provides believers with more peace, hope, perspective, truth, and courage than the existing cultural vision. One vision of ultimate reality triumphs over another. Above all, as a counter vision, Revelation points people to the true worship of the one true God, under whom all of reality fits into place.

Revelation’s symbolic language accomplishes its purpose by appealing in a unique way to the human imagination. By using language that is evocative and expressive, Revelation appeals to more than the intellect; it appeals to the whole person, emotions included. The entire affective dimension is engaged and transformed. Revelation does not just say something to us; it does something to us as well. Schüssler Fiorenza summarizes the evocative rhetorical strategy of Revelation:

"[Revelation] seeks to persuade and motivate by constructing a “symbolic universe” that invites imaginative participation. The strength of its persuasion for action lies not in the theological reasoning or historical argument of Rev. but in the “evocative” power of its symbols as well as in its hortatory, imaginative, emotional language, and dramatic movement, which engage the hearer (reader) by eliciting reactions, emotions, convictions, and identifications."

We are quick to add that there is no need for an either/or between theology and history on the one hand and the evocative nature of symbolic language on the other, between the meaning of the text and its meaningfulness or function. The two work together beautifully.

Both Bauckham and Koester use the example of John’s vision of the woman in Rev 17 to illustrate the transformative power of images. In John’s world, Rome was personified through various images as a noble lady, a city seated on seven hills, the goddess Roma in all her splendor and glory. According to the visual and auditory narrative of the day, she was worthy of devotion and worship. But John portrays her as a drunken whore sitting on a seven-headed beast. This seductively arrogant harlot amasses extravagant wealth and power in the process of deceiving and corrupting her devotees. Through the use of vivid imagery Revelation thus transforms the reader’s vision of ultimate reality and draws the reader deeper into faithful discipleship to Jesus.

It is important to keep in mind that the purpose of the imagery in the end is to reveal rather than conceal. Picture language provides a way of seeing spiritual reality—God, his character and his ways, the condition of the world, the church’s situation, and so on. Even more, such picture language calls the readers into obedient action. Hays writes, “The ethical staying power of the Apocalypse is a product of its imaginative richness.” The overall function is to exhort and encourage the audience to faithful discipleship. The symbols are not merely timeless objects for contemplation. This transforming vision confronts as well as comforts by engaging the whole person with the ultimate reality of the Triune God and his plans to make all things new. Readers are engaged by the imagery for the purpose of responding righteously in the world as followers of the Lamb. This helps us understand the opening beatitude: “Blessed is the one who reads aloud the words of this prophecy, and blessed are those who hear it and take to heart what is written in it” (1:3).

The Primary Contexts for Grasping Revelation’s Imagery

In subsequent chapters we will discuss further how to interpret Revelation’s imagery and the use of the Old Testament in Revelation. Here we simply note that there are two primary contexts for grasping the images and symbolism of the book, and neither is the contemporary context of modern readers. Both contexts are ancient. We have to begin with what it meant to them before we proceed to what it means to us.

First, John draws much of his imagery from the Old Testament and Jewish tradition. Revelation is saturated with Old Testament allusions that “frequently presuppose their Old Testament context and a range of connexions between Old Testament texts which are not made explicit but lie beneath the surface of the text of Revelation.” For example, John’s identification of the two witnesses in 11:4 with two olive trees and two lampstands points to the two anointed ones, Joshua and Zerubbabel, in Zech 4:1–14. As he sometimes does, however, John modifies the Old Testament allusion to suit his purposes. John sees two lampstands instead of one and he equates the trees with the lampstands. For John lampstands denote churches (Rev 1:20) and the imagery of the two witnesses likely refers to the Spirit “empowering his people with prophetic authority as a testimony against the nations.” Examples abound in virtually every paragraph of the Apocalypse as John draws on the Old Testament to give his picture language substance and authority.

John also mines the contemporary Greco-Roman context for his imagery, and this provides the second context for grasping his picture language. The churches of Asia Minor would have been able to pick up on such references. For example, Keener points to the Parthians and their reputation as fierce mounted archers as the likely background for the rider on the white horse in Rev 6:2 (cf. 9:14; 16:12 for other possible Parthian connections). Some interpreters associate “Satan’s throne” (2:13, ESV) with the altar of Zeus Soter in Pergamum. Other examples surface in the process of exegesis and interpreters would be wise to consider the possibility that the image derives from its local setting.

Thank you!

Sign up complete.